- Home

- Chris Frantz

Remain in Love Page 2

Remain in Love Read online

Page 2

I had a transistor radio and discovered Elvis Presley. He wasn’t known as “The King” yet. He was known as “Elvis the Pelvis” and he rocked the airwaves. “Hound Dog” was his massive hit of the moment and the radio would faithfully play it every hour both day and night. I really loved “Hound Dog,” but my mother would roll her eyes and tell me, “Oh, Chris! He is so common!”

I started kindergarten at Belfield School that fall. It was a brand-new small private school built on farmland. It was not unusual to see cows grazing right next to our playground. The classes were small and I made some new friends. I carpooled with my neighbors. One girl and her brother would come over to my house after school to play. She was a year older than I was and, if it was raining, we would go down to the basement to play. We would crawl under my father’s homemade desk and she would pull up her blouse and ask me to nurse from her nipples. She would ask me if I was getting any milk and I would stop and say, “No, not yet.” Then she would ask me to keep trying. This was her favorite game to play with me, but never with her brother. She told me that would be wrong.

I had a little bike with training wheels that I learned to ride. One day one of the neighborhood kids asked me if I would like to try his big boy’s bike. I should have asked him how the brakes worked before I started riding down the steep hill that we lived on. I remember panicking when I realized that I couldn’t stop. I just kept riding faster and faster until, finally, I sailed across busy Barracks Road at the foot of the hill, narrowly missing a farm truck, and crash-landed into an electrified, barbed-wire fence. I was pretty cut up from the barbed wire, and the front fender of the bike was all scratched and twisted. Cars whizzed by, but I bravely marched the bike back up the long hill, where the boy was waiting in front of our house with my mother. Relieved to see me still alive, she treated my cuts and scratches with Mercurochrome and Band-Aids. We got the boy’s bike fixed, but I still have a scar on one of my eyelids from that episode.

My mother made friends quickly in Charlottesville. Even though she was busy raising two young boys, she volunteered to work at Monticello, the home of Thomas Jefferson. The restoration of Monticello was an ongoing process and a very meticulous one. Still, there were over 200,000 visitors in 1957. I felt very happy as a six-year-old to be able to roam the grounds and surrounding forest unsupervised. There were all kinds of things to explore, like building sites, archaeological digs, and winding hillside trails. My mother told me, with great pride, that Thomas Jefferson was a distant cousin of ours and that made the dreamy summer afternoons we spent there all the more meaningful to me.

On the weekends that autumn my father would pick up a little extra cash as a high school football referee. He would put on his black-and-white striped shirt, hang a whistle around his neck, and off we would go in the Ford station wagon to schools like Woodberry Forest, Randolph-Macon Academy, and Staunton Military Academy. It was exciting for me to see my father, who always stayed in good shape, running up and down the field. He was a good referee. On the way home we would get a bite to eat somewhere. My father was always good about spending quality time with his children. His own father, Charton, had been just the opposite and, although they were married, had never actually lived with my grandmother, Gladys. Instead, Charton chose to live at the posh Pittsburgh Athletic Club. He owned a bakery and also a whiskey distillery in Berlin, Pennsylvania, called Old Man Frantz Whiskey. When my father was born in Pittsburgh, my grandmother took the baby and moved in with her parents. Her father, John Lewis, had come to Pittsburgh from Newfoundland, where his family had moved from the Isle of Jersey five generations before. They were Grand Banks fishermen who eventually migrated south to Pennsylvania, where the winters were not so long. I never heard my father say a bad word about his father, but he did tell me that his grandfather, John Lewis, was the one who raised him and gave him love and guidance.

Knowing my fondness for animals of all types, my parents gave me a gift of a white rabbit with pink eyes. I called him Pinky. My father built a fine rabbit hutch in the backyard that could be moved inside when the weather got cold. How I loved that creature! I would feed him rabbit food and give him water. We played together in the backyard every day until the day our neighbor’s Doberman pinscher, who was normally on a leash, swooped down, grabbed Pinky by the throat, and shook him ’til he was dead. There was much blood and violence and I blamed myself for not protecting the poor bunny. But I was only six years old and the Doberman was only doing what he had been bred to do. Not long after that I found a wild baby rabbit in my mother’s periwinkle beds. When there was no sign of a mother to save him, my own mother allowed me to keep him. He was a cottontail and lived with us for a good long while.

When my father completed his service at the JAG School, he retired from active duty in the Army, but remained an officer in the Army Reserve. He joined a law firm as a junior partner in his hometown of Pittsburgh, where he had many potential clients. We moved there at the end of my first-grade school year. While my mother was pleased about my father’s new job, she was not crazy about the idea of moving to Pittsburgh. She loved her life in Charlottesville and all of her friends there. It was a world redolent of history, society, antique dealers, writers, and Southern gentlemen and ladies. It was also a small town full of wild and interesting characters. William Faulkner was the artist-in-residence. When Faulkner’s fans would stop to stare at his home, hoping to catch a glimpse of the great man, he was known to come out of the front door, unzip his pants, and pee onto his lawn from the front porch. Teddy Kennedy was at the University of Virginia Law School. His admission to the law school was controversial because he had been expelled from Harvard for cheating. My mother was scandalized to hear that he had abandoned one of his dates on a dark country road late at night when she refused to have sex with him.

We all hated to leave Charlottesville. The last night we were there, after the moving men had packed up all of our belongings, we spent the night with my mother’s friend, Smitty, a real estate agent, who sent me out to the stream in her backyard to gather watercress for sandwiches. Being so young, I was not aware of how heavily she was drinking. She just seemed very happy to me. Later that night, after we had all gone to bed, we were awakened by bloodcurdling screams and the sound of footsteps running up and down the halls. My mother and father told me to stay in bed while they went to help Smitty, who was suffering full-blown delirium tremens. This was terrifying to Roddy and me, but my mother kept coming back to tell us that everything was going to be okay. Smitty’s son came to her rescue and took her to the hospital. The next day, on the long drive to Pittsburgh, I noticed that my mother was crying, but trying not to let us know.

Our first home in Pittsburgh was a little two-bedroom town house in a suburban development called McKnight Village in the North Hills, where a lot of young families lived. There were loads of kids my age and we did have fun together. We rode our bicycles for miles. We scaled massive granite walls. We climbed tall trees and sometimes fell out of them, knocking the wind out of our chests.

Musically, it was the heyday of the novelty song. Sheb Wooley’s “The Purple People Eater” and Brian Hyland’s “Itsy Bitsy Teenie Weenie Yellow Polka Dot Bikini” ruled the airwaves, but no song had greater impact than Chubby Checker’s “The Twist.” Everyone was twisting. There were Twist parties and Twist contests.

For a long time I was very happy listening to my parents’ collection of 78s. They had the Mighty Sparrow, Harry Belafonte, Blind Blake, and lots of other great Calypso artists’ records in boxes down in the basement. They had given me a portable record player that would play 78-, 45-, and 33-rpm records. They also gave me a little red plastic transistor radio that I would tune into rock and roll radio stations, like KQV, and the R&B station, WAMO. Like many other kids my age, I listened to the radio in bed at night, imagining that one day I would have a band with a song on the radio.

In 1961, when I was ten years old, I had a young friend who really loved to sing. He had a great voice,

deep for a child, but he was shy about singing in front of people. So he would take a long garden hose and sing into one end from behind some bushes while my friends and I would stretch out the hose and listen to his voice through the other end. The kid could really sing like a pro and was willing to sing a song over and over until we got tired of it. One day he sang us a song called “Big Bad John.” It was a spoken-word song, sort of a tall tale, about a big, powerful coal-mining hero. There were a lot of coal mines in Pennsylvania and the song seemed very real to us kids. My friend had memorized every word and I liked his a cappella version a lot. Later that same day, I heard the record on my little radio and the DJ said the song was recorded by Jimmy Dean. The backing track was coolly syncopated and reminiscent of Calypso with the sound of a chisel striking a rock in a mineshaft providing the accents. I rode my three-speed bike to Gimbels Department Store and asked for the 45 single version of “Big Bad John.” The lady who sold it to me said it was the number one record in the country. It was the first record I ever bought.

My mother and dad decided to build a house of their own in O’Hara Township. Kerrwood Farms was another new development with lots of kids my age. I was enrolled at Kerr School, which was walking distance from our new house. I remember this period of time so well. I was eleven years old and I was walking to school on a chilly, wet morning in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The sky was gray and flat looking. There was sleet coming down. I was wearing my white Safety Patrol strap and I was supposed to make sure that the other kids didn’t get hit by a car. It only took me about ten minutes to walk to school and all the other kids must have been running early or late because I didn’t see a soul. Music—“Walk Like a Man” by the Four Seasons—was looping around in my head. I was not feeling very cool at all since my mom made me wear galoshes that morning. I felt, I may not be cool today but one day I will be cool! I will be an artist, maybe even play in a band! I felt that One day, I will be respected and have something important and interesting to say. Girls will pay attention to me! I will go away from here and travel far and, when I come back, the girls will be in awe of my accomplishments and want to talk to me! They will think I am cool and they will want to sit next to me!

But, sadly, for now, I am only cool to the little kids who look up to me because I am a Safety Patrol who tells them when it is okay to cross the street. Then, as I turn the corner, I see Christine and Benedicte on their way to school. As I watch them walking together, I think they are the prettiest girls in the neighborhood. Then I see Dave, my best friend at the time. Dave waits for me to catch up. I notice that his mom has made him wear galoshes, too, so now I don’t feel so bad. We are both a little nerdy in our flannel-lined corduroy trousers and boxy, brown winter coats. Under our knit caps, we have crew cuts. Dave wears braces on his teeth and I wear a retainer. Dave is good at math and science, while I’m not sure I’m very good at anything yet. When we catch up with Christine and Benedicte, we say, “Hi,” and I notice that they do not have to wear galoshes. I also notice that their penny loafers are really wet and cold looking and have cinders stuck to them. In those days, the cinders from the steel mill furnaces were spread on the icy roads as traction to prevent cars from slipping and sliding. Anyway, Christine and Benedicte don’t care. They are giggling and cheerful and say hello to each of us by name. Christine is very tall, blonde, and willowy. She already has the beginnings of a woman’s figure. She also has a fantastic sense of humor. Benedicte has moved to our neighborhood from France. She is a slender, petite brunette with a kind of beatnik attitude. She wears a lot of black, unusual for a child in those days, and she seems to be aware of things the other kids were not aware of yet. Benedicte is cool and Christine is hot! I have a crush on both of them. As we reached the doors of Kerr School, the girls turn to us and say, “See you in band practice!”

There was more than one reason I loved band practice, and I did love it. We would have a couple of group lessons per week during regular classroom hours, and then we would practice all together as a band in the auditorium after school. When I arrived at Kerr, I had been trying to play the trumpet, but it wasn’t happening for me. It wasn’t for lack of trying. I put in the practice hours, but I wasn’t getting anywhere with my horn.

I was very fortunate to have a great band teacher named Jean Wilmouth. He was a mallet instrument guy himself, who played marimba, xylophone, and vibes. When I mentioned to him that I was getting nowhere on my trumpet, he said he thought I had a very good sense of rhythm, so why not try the drums? I just wanted to play music, so I said yes right away, and he gave me a pair of sticks and a practice drum pad, which was a rubber pad mounted on a piece of wood. Then he gave me a quick run through of drum rudiments and a beginner’s book and told me to start practicing. I did practice and I practiced hard. You begin with a single stroke roll, then you learn a double stroke roll, then a five stroke, then a seven stroke. I got good at these before I moved on to paradiddles and ratamacues. What, you may ask, is a paradiddle? It’s when you hit the drum one time with your left stick and again with your right stick and then twice with your left again. Then you hit it once with your right stick, once with your left, and twice again with your right. LRLL, RLRR, you repeat the pattern while slowly increasing the tempo, preferably with a metronome, until you have a smooth, repetitive pattern. The ratamacue is a single-stroke roll with a “drag” at the top of the pattern. It makes for a good basic drum fill. LRLR, RLRL. I got good at these, too. After a couple of months, I had a seat with the drum section of the school band. Boy, was I happy! Now, we are not talking drum kits or even rock and roll. We are talking one single snare drum on a stand. They always had the biggest guy play the bass drum, so that was not for me, although I did get to crash the cymbals from time to time. We learned to play songs by George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, and Scott Joplin. Particular favorites of mine were “Stranger in Paradise” by Alexander Borodin and “Begin the Beguine” by Cole Porter. We also performed a song that was at the top of the charts at the time called “Java.” It was recorded by New Orleans trumpeter Al Hirt and composed by the great Allen Toussaint. On that tune I played only the ride cymbal, but this was my introduction to the feel of syncopation, which was a real ear-opener for me. Now I could imagine beats that had rhythmic surprises that make people want to swing their hips and dance.

When I was twelve years old my little sister, Ruthie, was born. It was Sunday, May 26, and I had been an acolyte at church that morning. When my father pulled in the driveway, my grandfather Pappy came flying down the backyard stairs to tell us it was time to take my mother to the hospital. I had never seen him move so quickly. Roddy and I were so excited that we were actually jumping up and down. Later that evening, we got a call from our father telling us with great pride, “Chris and Roddy, you have a baby sister!” Ruthie, who got beauty and the brains! She would grow into a bright and beautiful woman with a good head for business who never fails to be kind, helpful, and understanding.

One Sunday evening in 1964, after dinner, my family was watching the Ed Sullivan Show as we did almost every Sunday. When Ed Sullivan introduced the Beatles to America in a theater of frenzied, screaming young girls, like many other young people I had an epiphany. This band made everyone feel that each song spoke directly to them. I sat there on the family couch watching them on our portable black-and-white television set with its rabbit-ear antenna and I was immediately transported to a better place. I felt warm and positively optimistic. Even my mother loved the Beatles, causing my father to tease, “Oh, Suzanne, you are such an Anglophile!” On the school bus the next morning, the girls were already singing Beatles songs in unison. The advent of the Beatles and “the British Invasion” that followed was, and still is, one of the most culturally important events of my lifetime.

In 1964, at Aspinwall Junior High School, my band teacher Mr. Springman believed that band class was just as important, if not more so, as any other academic subject and he ran a tight ship. If you weren’t with the program, he kicked you

out. I was thrilled when he asked me to create a marching cadence for the band’s appearance in the Memorial Day parade. I still remember it, too.

I joined a group of friends from the school band to play some rock and roll and impress the girls. Lloyd Stamy was and still is a real go-getter. Together with some other school bandmates, he created the first rock and roll band I was a part of. Lloyd was the lead singer and also played trumpet. Ernie Maynard played trombone. Ray Bayer, who played clarinet in the school band, was on electric guitar. Herbie Purcell played a bass guitar. At some point Tom Kleeb joined us on guitar, too. We mostly just practiced a lot, learning a repertoire of Beatles, Beach Boys, Dave Clark Five, and Ventures tunes, as well as the Kingsmen’s “Louie Louie” and Johnny Rivers’s “Secret Agent Man.” Because we had horns, we could also play hits by Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass.

Family Portrait, 1963.

The band was called the Lost Chords, which I still think is a very cool name. One Sunday summer afternoon, we were rehearsing at my house with the windows open. Nobody had air-conditioning back then. We were playing our thirteen-year-old hearts out when a police car rolled up to our house. The officer said we’d have to stop because he’d had complaints from a neighbor. My mother took control of the situation and told the officer, “You should be ashamed of yourself. These are good boys playing good music. Nobody should be bothered by that on a summer afternoon. Don’t you have anything more important to do?” The chagrined cop said, “Well, don’t play too much longer,” and left. I can only remember playing one show with the Lost Chords. It was a Youth Fellowship Dance at the Fox Chapel Presbyterian Church. How clean cut can you get? Still, the experience of playing rock and roll with those guys sparked a lifetime love of playing live music and for that I’m very grateful.

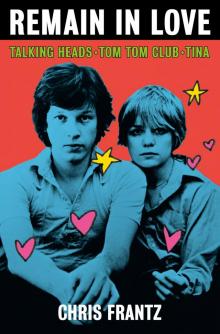

Remain in Love

Remain in Love